Brief biography

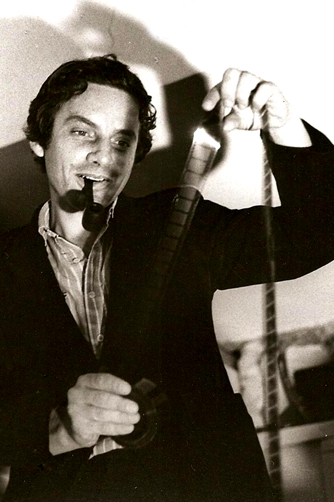

Rogério Sganzerla

Rogério Sganzerla was born on 4 May 1946, in Joaçaba, in the interior of Santa Catarina state. The third child from the marriage of Albino and Zenaide Sganzerla, Rogério had five brothers and sisters. He was a shy and quiet child, and from a very early age showed a vocation for cultural activities. The provincial environment of his city contrasted with his personality, marked by interests such as reading and writing. At the age of 8, he printed a typography of a small book of stories called Contos Novos.

In his teenage years, studying at the Jesuit boarding school of Colégio Catarinense, in Florianópolis, he was advised by Father Décio Andriotti to participate in the cultural activities of the institution, to make up for his lack of interest in physical activities. When he moved to the state capital city, he began frequenting film clubs, coming into contact with the works of filmmakers such as Robert Bresson, whose film Un condamné à mort s'est échappé he watched five times. At the time, he still had not seen on the silver screen the works of the filmmaker, who would have such a profound influence on his film career. Cinema thus began to figure as a major part of his cultural universe. During this period, he wrote scripts and made a small homemade film that registered every day events in his home city.

In 1964, he moved to São Paulo to study Law and Business Management, and wasted little time initiating his professional career as a film critic in the Literary Supplement of the O Estado de São Paulo newspaper. At the paper, his colleagues included the renowned Décio de Almeida Prado and Francisco Luis de Almeida Salles, who both quickly spotted his intellectual capacity at such an early age - Sganzerla was already a mature critic, despite his young age (17). He was a cinema thinker, analyzing issues pertinent to the filming process and the language studies/research of this form of modern expression. Regarding this period, Sganzerla said that "I did cinema by typewriter".

In 1966, he started to film what would be his first professional work in the cinema: Documentário (Documentary) which despite its name is a short fiction film that already served as a preview of his later work. Documentário is a formal exercise that narrates the aimless wanderings of two youths around the streets of São Paulo for whom cinema was their raison d´être. With this debut film, he won the prize for best short film at the first JB-Mesbla Amateur Film Festival, giving him the opportunity to study cinema in France. Now working as a journalist of the Jornal da Tarde newspaper, he used the opportunity to cover the 1967 Cannes Film Festival and travel to other European countries, and to improve his knowledge of local film trends and cultures.

Upon returning by ship to Brazil, after his brief European stint, Rogério Sganzerla read in the Brazilian newspapers available onboard, news about João Acácio Pereira da Costa, the "Bandido da Luz Vermelha", who was terrorizing the city of São Paulo. He shortly realized that, coincidently, the real-life character of the police chronicles bore an uncanny resemblance to the character of a script about a masked bandit that he had been working on for some time.

He started filming O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (The Red Light Bandit) in the second semester of 1967, with a full team comprising the photographers Peter Overbeck and Carlos Ebert, and actor Paulo Villaça, on his cinema debut, in the role of the street bandit. The cast also featured the actor Pagano Sobrinho, interpreting a populist and corrupt politician, and Helena Ignez, at the time considered the "Muse of the New Cinema", in the role of a conniving prostitute. Rogério and Helena initiated, behind the scenes, a loving and artistic relationship that would endure until the filmmaker´s death. In the editing process, Sganzerla hooked up with Sylvio Renoldi, who contributed greatly to constructing the discontinuous and fragmented narrative that the script required, explaining the originality of the tape, which was considered a blockbuster by critics and at the box-office.

O Bandido da Luz Vermelhahas since become one of the most expressive films of all time and the ultimate emblem of the saying "Marginal Cinema", a denomination always rejected by the director himself. Before its launch, Rogério Sganzerla had written a manifesto in which he listed the premises of the type of cinema that he planned to make in Brazil. Oswald de Andrade referred to the general lines of the text, pointing out that the appropriation of Godard, Welles, rock, comic books, US cop "B" movies, as well as other references of the movie, were testament to its link to an anthropophagic perspective, also defended by the tropicalista movement, a peer in the cinematographic movement.

After the success of his debut feature film, Rogério Sganzerla began, in 1969, devoting his time to a new project that would prove to be his biggest box-office success: A mulher de todos (The Woman of Everyone), with Helena Ignez as the lead character, in a benchmark performance in the history of Brazilian cinema. With the aim of reviving the tradition of chanchada - a national school of cinema scorned upon by the Cinema Novo, a movement he would later oppose from an aesthetic standpoint - Sganzerla invited Jô Soares to play the role of the husband, a successful businessman from the comic book publishing business and ex-Nazi henchman, cheated on by the lead character Ângela Carne e Osso. Continuing with the comic book theme, in the same period he made two short documentaries with Álvaro de Moya: HQ and Quadrinhos no Brasil. At the showing of A mulher de todos at the Brasília Film Festival that year, he befriended Júlio Bressane, who was presenting O anjo nasceu (The angel was born).

This meeting would prove pivotal. In early 1970, living in Rio de Janeiro, and in partnership with Bressane and Helena Ignez, Rogério Sganzerla founded the production company Belair, which produced, in total, some six films in the space of three months. The films directed by Rogério are Copacabana Mon Amour (with original soundtrack by Gilberto Gil), Sem essa, Aranha (Give me a break, Spider) (with Jorge Loredo [Zé Bonitinho], Helena Ignez, Maria Gladys and Luiz Gonzaga in the cast) and Carnaval na lama (or Betty Bomba, a exibicionista), partly filmed in New York. These films further deepened the experimentalism that was already a characteristic trait of his cinema: new possibilities were explored in the director/actor relationship, language exercises became more radical - as shown by the long sequences of Sem essa, Aranha.

Before starting editing work on the films, the Belair headquarters was secretly alerted that if it remained in Brazil, which at that time was under the shadows of AI-5, they would be arrested. Exiled, Sganzerla left with Helena and Bressane to London. There entered the fold of the local community of expatriate Brazilian artists including Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Jorge Mautner, Antonio Bivar, Jards Macalé and others. In this stint in Britain, Rogério filmed the show of Jimi Hendrix at the Isle of Wight Festival. In 1971, he and Helena traveled to Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Niger, Nigeria, Benin and Senegal, where they led a nomadic life for some time. Sganzerla used the opportunity to film the documentary Fora do baralho, whose backdrop was the Sahara Desert.

Back to Brazil, in Salvador (Bahia) to be exact, after a 2-year exile, Helena Ignez gave birth to her first daughter with Rogério Sganzerla, Sinai, in October 1972. A period of relative inactivity had begun shortly before his return to the country due to the cinematographic policy in place at the time. The director had already assumed a combative stance, since 1969, in relation to the official entities regulating cinema and their respective representatives, who he held responsible for hatching plots to sabotage his films. This dispute persisted throughout his career.

Back in Rio, Sganzerla only returned to cinema in 1976, firstly with the short film Viagem e descrição do Rio Guanabara por ocasião da França Antártica (Voyage And Description Of The Guanabara River At The Time Of France Antarctic, about the journey of the adventurer Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon to Rio de Janeiro in the 16th century and, then, with Abismu (The Abyss), a feature film again starring Jorge Loredo as Zé Bonitinho in the cast and, also, José Mojica Marins and Wilson Grey acting to a soundtrack of Jimi Hendrix.

February 1977 saw the birth of the couple´s second daughter: Djin. In this period, Rogerio also filmed the short documentaries Mudança de Hendrix (Hendrix Change) and Ritos populares :– Umbanda no Brasil. In 1978, he worked as co-director and editor of the mid-length documentary in Super-8 technology, Horror Palace Hotel, directed by Jairo Ferreira, in which he also appears as a reporter interviewing his colleagues Almeida Salles and José Mojica Marins.

In this period, Rogério Sganzerla spent time in Rio and Salvador. After making several short films, such as Noel por Noel (Noel Rosa by Noel Rosa), his first film about the composer Noel Rosa, Sganzerla returned to feature films with Nem tudo é verdade (It's not all true), in 1985, which initiated his tetralogy on Orson Welles´ 1942 visit to Brazil. The musician Arrigo Barnabé played an Orson Welles aged 25, at the height of his international fame as the genius creator of Citizen Kane, who traveled to Rio de Janeiro to film the Carnival. A mixture of documentary and fiction, Nem tudo é verdade garnered numerous awards.

From 1986 onwards, Rogério Sganzerla settled down for good in Rio de Janeiro. In 1990, he directed the short film Isto é Noel Rosa (This is Noel Rosa) and made two videos about artists: A alma do povo vista pelo artista (Newton Cavalcanti: the people's soul), about Newton Cavalcanti, and Anônimo e incomum (Anonymous and Uncommon), about Antonio Manuel. In 1987, he launched the second part of the Orson Wells series with the short film Linguagem de Orson Welles (The Language of Orson Welles). In 1993, he directed the episode Perigo Negro (Black Peril), which is part of the feature film Oswaldianas, based on Oswald de Andrade. In 1998, he launched the full-length documentary using collated images and audio, entitled Tudo é Brasil (All is Brazil), the third part of his tetralogy on Orson Welles.

In 2001 he published a selection of critiques: Por um cinema sem limites, which is the reaffirmation of his cinematographic ideal. In 2003, after much struggle, he concluded O signo do caos (The Sign of Chaos), the last film in the series on the visit of the director of Touch of Evil to Brazil, and which was also his last film. The cast also included his daughter Djin Sganzerla, in her first cinema role. It was launched at the Festival of Brasília, where it won the Best Editing and Best Directing awards. It also won the Special Award of the Rio Film Festival. Rogério attended the screening of the film at Cine Odeon, despite being debilitated by the effects of a devastating cancer.

Rogério Sganzerla passed away on 9 January 2004. He left a large body of work yet to be filmed, comprising scripts and projects of films, and also a vast volume of critique: articles and essays, both published and unpublished. One of the scripts is the feature film Luz nas trevas :– Revolta de Luz Vermelha (Light in darkness), a continuation of the saga of Bandido da Luz Vermelha. Using a shortened version of this script, five years later, filming began with Ney Matogrosso in the role that had been played by Paulo Villaça, now with Helena Ignez as director.

Posthumously, Rogério Sganzerla has received several tributes and retrospectives at various Film Festivals around the world. His work continues to shine on.